While the record is certainly not blank with regard to a history of powerful and influential women — Catherine the Great, Joan of Arc, Catherine de Medici, Eleanor Roosevelt, Queens Victoria and Elizabeth, Rosa Parks, Cleopatra — nowhere does a graphical depiction of absolute equality between the sexes exist with such profudity as that which still stands at the Temple Complex of Merowe in Northern Sudan.

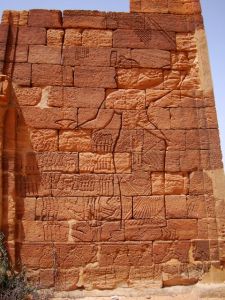

Here, on the left hand wall of a massive, 20-ft high bas relief, a male pharoah raises his sceptre to smite the knot of enemy heads he grasps by the hair. In traditional Egyptian iconography, the pharoah stands three or four times the size of those he is about to kill, a statement of his superiority and a nice artistic touch to allow the masses in their domination to be better portrayed, often literally, under foot. The pharoah’s dog waits, teeth bared, between his legs to feast on the carcasses of the slain.

This bas relief itself really doesn’t depart too widely from many of the other Egyptian retellings of war conquest. What sets it apart is the matching right-hand panel of this same wall. Here, the queen partakes in a very equal-opportunity sort of slaughter, with an equal number of enemy prisoners gathered by their locks in her hand while her other arm — this time with sword rather than with sceptre — hovers menacingly above them.

The best part of all of this, the part that stands in such stark contrast (an almost ‘Not Quite Right‘ sort of contrast) when compared to the lithe images of other female Egyptian rulers like Nefertiti, is this woman’s stylized yet very full, very womanly figure. It is nice to see power displayed in such a way: equal, unsparing, and devoid of the expectation that a woman in power rules through guile or charm rather than through the sort of brute physicality this long-gone pair of pharoahs demonstrated.